Life with IBD

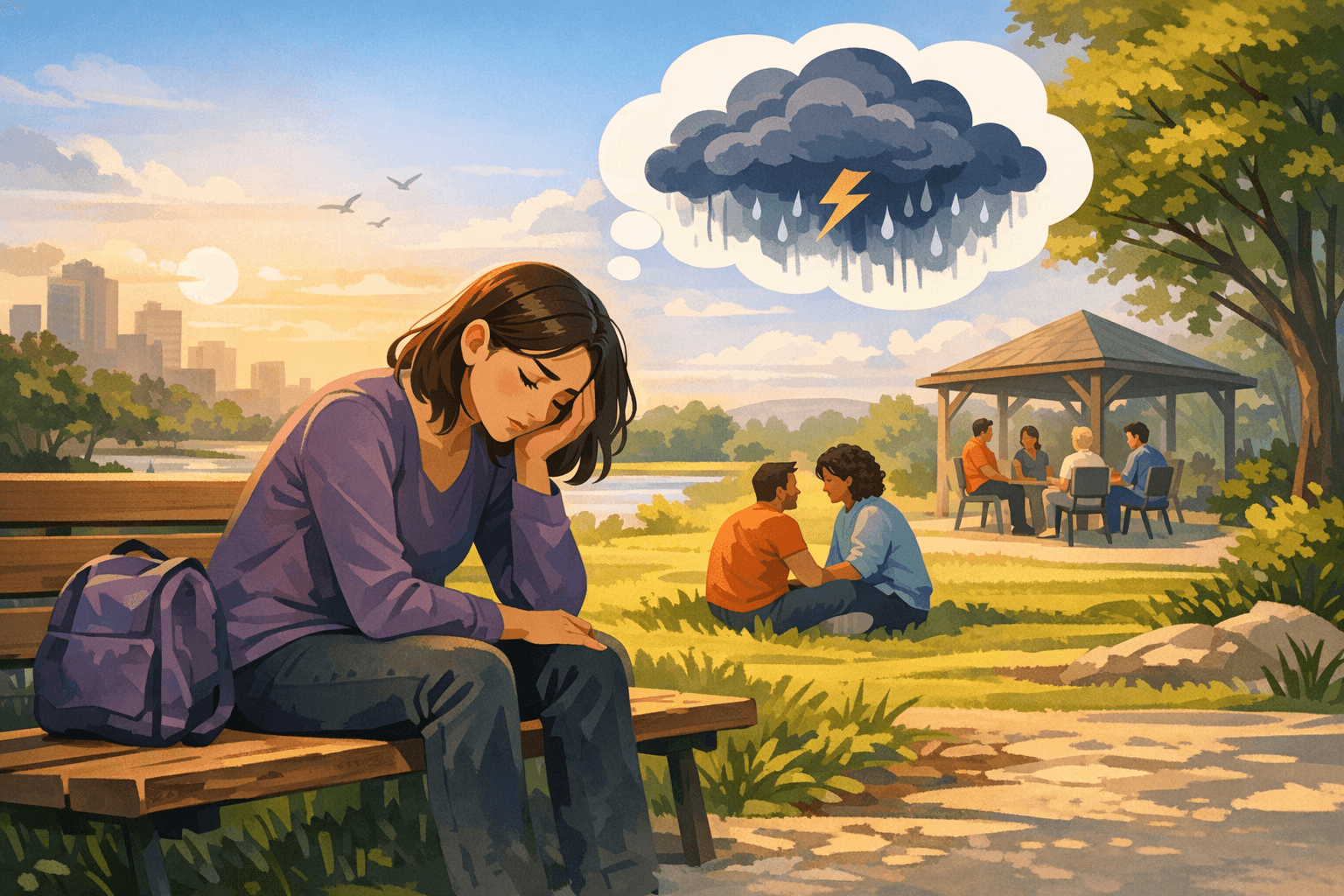

Living with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affects far more than the digestive tract. Anxiety, depression, and day to day stress are very common, especially around flares, uncertainty about symptoms, and life changes like work or school. Mental health conditions are treatable, and support can come from professionals, peers, and simple daily habits that protect emotional well being alongside gut health.

Key Takeaways

Anxiety and depression are more common in IBD than in the general population, especially when disease is active. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

The brain and gut communicate in both directions, so inflammation, pain, and stress can all influence each other. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Evidence based therapies such as cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness programs can reduce distress and disability in IBD. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Mental health support can come from psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, and specialized psychogastroenterology providers. (crohnscolitisfoundation.org)

Peer and community support, including IBD specific support groups and helplines, often helps people feel less alone and more empowered. (crohnscolitisfoundation.org)

How IBD and mental health are connected

IBD is a long term condition that often starts in young adulthood, a time filled with education, work, relationships, and family planning. That timing alone can increase emotional strain. Large reviews suggest that about 1 in 5 people with IBD meet criteria for an anxiety disorder, and a similar proportion for depression, with even higher rates of milder symptoms. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Symptoms tend to be worse when IBD is active. Studies find that people with flares have roughly double the rates of anxiety and depression compared with those in remission. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) Anxiety and depression are also common right at diagnosis, when people are adjusting to new tests, medicines, and information. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

The link is not only emotional. The brain and gut communicate through nerves, hormones, immune signals, and the gut microbiome, often called the brain–gut or microbiome–gut–brain axis. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) Inflammation, pain, poor sleep, and certain medicines (such as corticosteroids) can all affect mood. In the other direction, chronic stress, anxiety, and depression can worsen pain, bowel symptoms, fatigue, and adherence to treatment. (academic.oup.com)

Mental health conditions in IBD are common, medical, and treatable. They are not a character flaw or a sign of weakness.

Anxiety in IBD

What anxiety can look like

Anxiety in IBD often centers on:

Fear of urgent bowel movements or accidents

Worries about finding bathrooms when away from home

Concerns about flares, colonoscopy results, or long term complications

Stress about work, school, parenting, or relationships with unpredictable symptoms

Common signs include:

Body symptoms: racing heart, muscle tension, sweating, shakiness, stomach discomfort

Thoughts: constant “what if” worries, expecting the worst, strong focus on symptoms

Behaviors: avoiding travel, social events, or dating, repeatedly checking bathroom locations, difficulty starting tasks

Some people experience panic attacks, with sudden intense fear, chest tightness, shortness of breath, or dizziness.

Helpful supports for anxiety

Several approaches have evidence in IBD:

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Group CBT tailored to IBD has been shown to reduce anxiety and depression and improve quality of life, and even to reduce markers like C reactive protein in some studies. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Mindfulness based programs. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy has reduced psychological distress and improved well being in a randomized trial, with possible benefits on sleep and inflammation. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

IBD specific CBT by telehealth. An 8 week telehealth CBT program lowered IBD related disability, independent of disease activity. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Health care teams may also consider medicines for anxiety, especially when symptoms are severe or persistent. These choices are usually coordinated among gastroenterologists, primary care clinicians, and mental health specialists.

Depression in IBD

How depression feels

Depression is more than feeling sad about a flare or bad test result. It usually involves several of these for at least a couple of weeks:

Persistent low mood, emptiness, or irritability

Loss of interest in usual activities or relationships

Changes in appetite or weight

Trouble sleeping or sleeping too much

Marked fatigue or lack of energy

Feelings of guilt, worthlessness, or hopelessness

Difficulty concentrating or making decisions

Thoughts that life is not worth living, or thoughts of self harm

In IBD, depressive disorders affect roughly 15 percent of patients, and depressive symptoms are even more common, especially in Crohn’s disease and during active inflammation. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Treatment options

Evidence based treatments include:

Psychotherapy. CBT, interpersonal therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy can all help people adjust to chronic illness, manage negative thoughts, and rebuild daily activities. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Antidepressant medicines. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and related medicines are often used in chronic illness. Choice of drug, dose, and timing should be individualized and monitored by a clinician familiar with both mental health and IBD.

Lifestyle measures. Regular physical activity, better sleep, and limiting alcohol can support mood, although they are usually not enough alone for moderate or severe depression. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

If someone has thoughts of self harm or suicide, this is an emergency. In the United States, immediate help is available by calling 911, going to the closest emergency room, or contacting the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (phone, text, or online chat). (crohnscolitisfoundation.org)

Working with mental health professionals

Who can help

Several types of professionals may be involved:

Psychologists and other therapists, who provide structured talking therapies such as CBT

Psychiatrists, who can diagnose and prescribe psychiatric medicines

Licensed counselors or clinical social workers, who offer counseling and support around stress, relationships, work, and coping

Psychogastroenterology specialists, mental health clinicians with specific training in digestive diseases and the brain–gut axis (nationalpsychologist.com)

IBD clinics and the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation list directories of mental health providers experienced with digestive disorders and chronic illness. (crohnscolitisfoundation.org)

What early visits often cover

An initial visit usually includes:

Background on IBD history, recent flares, and treatments

Screening questionnaires for anxiety, depression, and quality of life

Discussion of main stressors, supports, and goals

A shared plan, for example 8 to 12 CBT sessions or a mindfulness group

Good care involves coordination. With permission, mental health clinicians often communicate with gastroenterology teams so that treatment plans fit together.

Community and peer support

Professional care is important, but many people also benefit from connecting with others who live with IBD.

Examples of community options include:

Local and virtual support groups. The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation hosts more than 200 support groups across the United States, including virtual groups, pediatric programs, and targeted groups such as ostomy or young adult support. (crohnscolitisfoundation.org)

Peer mentoring. Programs like the Foundation’s “Power of Two” match patients or caregivers for one to one support by phone or online. (crohnscolitisfoundation.org)

Online communities and forums. Foundation hosted communities and other moderated forums allow people to share experiences and coping strategies. (crohnscolitisfoundation.org)

Helplines. The IBD Help Center provides education, resource navigation, and referrals by phone, email, or chat. (crohnscolitisfoundation.org)

Helpful support spaces usually have clear rules, respect privacy, discourage personal attacks, and remind members that peer stories do not replace medical advice. If a group leaves someone feeling more hopeless, judged, or overwhelmed, it is reasonable to limit time there and look for a better fit.

Everyday coping strategies

Daily routines can protect both mental and gut health, even while formal treatment is underway.

Helpful habits may include:

Structured days. Regular times for waking, meals, movement, work or school, and winding down can reduce stress on the brain–gut axis.

Gentle activity. Walking, stretching, or low impact exercise most days can support mood, sleep, and bone health, adjusted to energy levels and medical advice. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Simple stress tools. Brief breathing exercises, muscle relaxation, or short mindfulness practices, even for a few minutes, can lower physical arousal and symptom related anxiety. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Symptom and mood tracking. Apps or journals that log bowel habits, pain, sleep, and mood can help people spot patterns and share clearer information with clinicians.

Communication and planning. Talking with family, friends, schools, or workplaces about IBD, and using tools such as restroom access cards or accommodation letters, can lower worry about accidents or missed time.

Over time, combining medical treatment of inflammation with attention to emotional health, social support, and practical planning offers the best chance for a fuller, more stable life with IBD.

FAQs

How common are anxiety and depression in IBD?

Large reviews suggest that about 20 percent of adults with IBD meet criteria for an anxiety disorder and about 15 percent for a depressive disorder, with even higher rates of milder symptoms. Rates increase during active disease and soon after diagnosis. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Can treating mental health improve gut symptoms?

Psychological treatments such as CBT and mindfulness based therapies in IBD have been shown to reduce distress, disability, and sometimes markers of inflammation or disease activity, although they do not replace standard medical therapy. (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) Addressing mental health is best seen as part of whole person care.

How can family and friends support someone facing IBD and mental health challenges?

Supportive relatives and friends can listen without judgment, learn basic facts about IBD, offer help with practical tasks, and encourage professional care when needed. Respecting the person’s own treatment choices and avoiding pressure to try unproven “cures” can also protect trust and emotional well being.